Introduction (?): Affect is Dead! Long Live Affect!

Every act of writing, reading, and analysing literature should be a libidinal vivisection of “the so-called body”, as philosopher Jean-François Lyotard describes in the opening to his 1974 Libidinal Economy: “Open the so-called body and spread out all its surfaces” (1). When we, human bodies that affect and are affected, open or unfurl either digital or paper bodies of work, there should be a shared affective resonance of these two bodies, akin to what philosopher Karen Barad terms “intra-action” (141). In this dissertation, I will explore the “intra-activity” of affects (Barad 152) in Lyotard’s Libidinal Economy and Romanian writer Mircea Cărtărescu’s 2015 novel Solenoid. Through this, I draw inspiration from Ross Benjamin’s 2023 translation of Franz Kafka’s Diaries, in which Benjamin argues that Max Brod, friend and “literary executor” of Kafka’s bodies of work “presented the diaries to the extent possible in the guise of a Werk, a cohesive and fixed work, rather than Schrift, writing as a fluid, ongoing, godless activity” (ix). In this dissertation, I will argue that Libidinal Economy and Solenoid are bodies of Schrift that still affect us. In contrast, bodies of Werk portend to be a simulacrum of affect, reinscribing the mantra: Affect is Dead! Long Live Affect!

In this dissertation, I will focus on Lyotard’s arguably most affective and polemical text, Libidinal Economy, as a shadowy example of a body of Schrift. By this, Libidinal Economy was written in the style of what Keith Crome calls an “affective nihilism” and belongs to what translator Iain Hamilton Grant called a “short-lived explosion of a somewhat naïve anti-philosophical expressionism” (“Introduction” xviii). The text was written quickly and as a vitriolic response to the failures of Marxism, specifically the PCF’s responses to the May 1968 protests in France, in which Lyotard, an active member of 1968, expressed his disdain for Marxists and their inability to join the streets. It was a text written out of a cathartic need to exorcise the spectres of 1968 and propose a body politic of neither good nor bad libidinal intensities. At its core, Libidinal Economy is a text that reinscribes the paradoxical tenet of poststructuralism, critiquing the notion of representation through the medium of language. However, Lyotard is not writing to propose a new philosophy to interpret or change the post-1968 world, but rather an affectively charged nihilistic polemic.

Throughout Libidinal Economy, Lyotard uses a variety of paradoxical models that attempt to display what is excluded by representational thinking. To avoid being trapped in Plato’s allegory of the cave, Lyotard opens the text with the violent and sexually explicit vivisection of an ambivalently sexed body; the organs are ripped out, the entrails elasticised around the pages, and the skin is flattened and stretched out into what he terms the “libidinal band/skin”. The libidinal band/skin resembles a Möbius strip that spins in an aleatory manner, circulating the labyrinthine white-hot intensities of desire, which, for Lyotard, cannot be represented through language but only felt as affective intensities (4). The band is similar to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s concept of the body without organs from Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Crucially, however, although Lyotard maintains that desire is not based on a psychoanalytic lack, desire is not a productive assemblage of what Deleuze and Guattari call “desiring-machines” (Anti-Oedipus 16), but rather it is politically ambivalent and destructive. The band has neither an inside nor an outside and cannot be considered “’descriptively’ true (since the model would then collapse back into re-presentation” (Grant “Glossary” xii). In 1988, Lyotard reflected on Libidinal Economy and sardonically called it his “evil book, the book of evilness that everyone writing and thinking is tempted to do”, a text of “anger, hate, love, loathing, [and] envy” (Peregrinations 13). Through this, I want to propose my own dissertation, “of evilness”, by returning to the title of this introduction: Affect is Dead! Long Live Affect!

In my Personal Statement to university, I began by quoting the introductory question from literary theorist Terry Eagleton’s 1983 Literary Theory: An Introduction: “What is Literature?” (1). After four years of study, I have found my answer: Literature, specifically anglophone literature, has lost any form of affective or emotive resonance insofar as anglophone literature is just brightly packaged and derivative shite. In the 21st century, our bodies, that affect and are affected, are subjected to an inundation of affect from doom-scrolling on Twitter and TikTok to True Crime documentaries to browsing Waterstones or navigating Amazon’s bestseller list; a Borgesian Library of Babel surrounds you that unfolds to the infinitude of disappointment; it denies any possibility of literary jouissance. This abundance has caused a numbing of affects; we are no longer affected by what we read, feel, smell, touch, taste, hear, or see. We are no longer experiencing what Frederic Jameson lamented in the 1990s a “waning of affect” (11); affect has waned. Completely. Numbed. Dead. Kaputt. Affect is Dead! Long Live Affect!

However, I do not mean dead in the sense that affect is buried, but rather that our bodies have lost the ability to be affected; the nerve endings are dead. Burned off. Everything published by Anglophone publishers is too formulaic, from MFA-produced dribble to trauma-porn to stories about toxic situationships. Anglophone literature is trapped in the nihilistic confines of what Lyotard calls the “great Zero” (LE 5), the zone where there is only a singular narrative, which is nihilistic. Affect is, therefore, unmoving, at absolute zero, −273.15 °C, ossified as a body of Werk. In this dissertation, I have turned away from anglophone literature and, through surrealist objective chance, stumbled into the labyrinthine worlds of Cărtărescu 2015 maximalist hypobiography Solenoid. However, the labyrinthine worlds of Cărtărescu are not Daedalian, where we, the reader, can hang on tight to Ariadne’s Thread; instead, we become like rats trapped in a maze, yearning for cheese and escape.

I borrow the term “hypobiography” (355) from Lyotard’s 1996 Signé Malraux1 to explore how Cărtărescu does not construct what Doris and Andrea Mironescu coin “maximalist autofiction” (66). Unlike autofictional authors like Karl Ove Knausgård or Annie Ernaux, Cărtărescu does not just present an autofictional account of his life but opens up his body of Schrift to transform the hypothetical projection of what his life might have been if he had not achieved literary fame and success, through the nameless anti-narrator, whom I term anti-Mircea. Solenoid was written in one draft without revision and presented as a manuscript by his hypobiographical Other. This hypobiography arises as an example of what Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges describes in his 1944 short story “The Garden of Forking Paths”, whereby Cărtărescu, aged 21 in 1977 whilst a student at the Bucharest Faculty of Letters, presented a 30-page epic poem titled The Fall to the famous Romanian literary group the “Monday Circle”. The Fall was hailed as a masterpiece by the chair of the circle, the Romanian literary critic Nicolae Manolescu. However, in Solenoid, The Fall is not a success; it is lambasted as a failure by the fictionalised “Workshop of the Moon” and leads anti-Mircea to follow a different, more dangerous, and sinister path. Solenoid is in many ways the greatest surrealist novel never written, as anti-Mircea’s manuscript functions as an anti-literary example of what surrealist writer André Breton describes as “[p]sychic automatism in its pure state” (26); it exemplifies a body of Schrift that attempts to find escape from the mundanity of anti-Mircea’s life. Therefore, just as Lyotard proposes, “let’s make theory anti-theory” (LE 257), Cărtărescu/anti-Mircea proclaim: “Let’s make literature anti-literature”.

“A book should demand an answer”: Descending into Anti-Mircea’s Labyrinthine Skin

In this first chapter, I want to respond to anti-Mircea’s statement that “a book should demand an answer” (210) as an entry point into vivisecting the labyrinthine skin of anti-Mircea, the literary career of Cărtărescu, and how Cărtărescu opens the body of literature and spreads it out amongst the pages of Solenoid. Consequently, in this chapter, I will first trace the thematic and stylistic similarities between Cărtărescu’s first 1989 “novel” Nostalgia, and Solenoid, under the rubric of what Matt Weir describes as “Mircea Cărtărescu [is] staring into an abyss” (113). Secondly, I want to analyse the maximalist hypobiographical style of Solenoid and its theoretical relationship to the postmodern as presented differently by Jameson and Lyotard. Lastly, I want to claim that the failure of The Fall in Solenoid leads to the creation by Cărtărescu of a character which echoes Friedrich Nietzsche’s Zarathustra in Thus Spoke Zarathustra; however, Cărtărescu does not decry the death of God, but rather the death of literature.

Falling into the Abyss: Nostalgia to Solenoid

In an interview with Sean Cotter, translator of Solenoid, at the Bass School at UT Dallas, Cărtărescu spoke about the influence of his epic 1977 poem The Fall as the impetus for anti-Mircea’s forking path, which diverges away from literary fame and into the labyrinthine skin of Solenoid. Cărtărescu claimed that his transition from a poet to a novelist occurred due to “poetry being an art of [the] youth” (1:00:33-1:00:40). Consequently, The Fall functions as the original descent into the labyrinthine cartography of Solenoid. However, The Fall has yet to be translated into English other than extracts found in Solenoid; therefore, when tracing the evolution of Cărtărescu as a writer, we can only treat Cărtărescu as a writer from the old, from Nostalgia to Solenoid. Through this, as Weir argues, “Cărtărescu [is] staring into an abyss” (113). However, Cărtărescu is not just a writer who is staring into the abyss, but swimming, crying, and writing into the abyss; from his first “novel” Nostalgia to Solenoid, Cărtărescu has maintained an anti-literary style that is violent vivisection on the body of literature, to the extent that Cărtărescu is a writer who is writing on the libidinal skin of literature. Every body of Cărtărescu’s work and all other bodies of literature are flattened and spread open in the pages of Solenoid to expose the fallacy of representational thinking.

Nostalgia was initially published and titled Visul (The Dream) in 1989, then published in full as Nostalgia in 1993, and in 2005 it was translated into English and billed as a “novel”. I place “novel” in dubious quotation marks as Nostalgia is not a novel like Solenoid but a collection of five tenuously connected short stories unfolding in the underbelly of late-20th-century communist Bucharest. Nostalgia begins with the prologue, “The Roulette Player”, then it shifts into three short stories/novellas, Mentardy, The Twins, and REM, and ends with the epilogue of “The Architect”. The narrative voices of “The Roulette Player” and anti-Mircea are metatextual inverses of one another. The prologue is narrated by an old, fictional, failing writer written by a young, soon-to-be-successful novelist, Cărtărescu. In contrast, Solenoid is narrated by a young, fictional, failed writer written by an old, already-successful novelist, Cărtărescu. This metatextual similarity between the two narrators may indicate what Deleuze and Guattari describe as rhizomatic, which “has no beginning or end” (Plateaus 25). Cărtărescu’s narrators, however, are not positive reorganisations of narrative but are instead trapped in what Lyotard describes as Plato’s cave of representation: “an entirely closed theatre” not to be confused with our “Moebian-labyrinthine skin” (LE 4).

The prologue describes a man who continuously beats death in games of Russian Roulette; the narrative is interrupted by the titular roulette player worsening his odds by announcing a “roulette with four bullets thrust into the chamber’s alveoli, and then, with five” (18). The game continues until it is loaded “with all six bullets” (20): the game of life or death is now a game of death or death. The unnamed narrator of “The Roulette Player” describes how he has “written a few thousand pages of literature – powder and dust” (4) because the tales of the criminal underbellies of Bucharest are greater than anything he could write. However, Cărtărescu subverts the inevitability of death, and the roulette player absconds from the labyrinthine underbellies of Bucharest, never to be heard of again. In an interview I conducted with Cotter in March 2024, I brought up the anti-literary narrative voice similarities between “The Roulette Player” and Solenoid and asked at what point does “each subsequent book you write add another bullet to the author’s chamber”, to which Cotter replied, “he’s written more than six now”, and is therefore, on borrowed time. Cărtărescu is an author staring down the now-overfilled chamber and, like the roulette player, continues not just to stare into the abyss but to write into it.

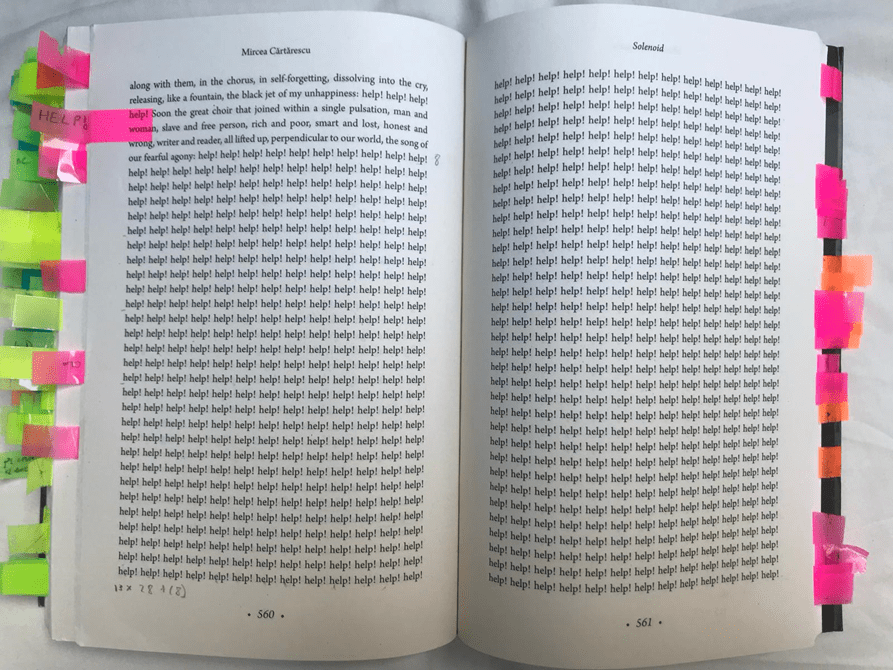

Weir’s imagery of “Cărtărescu staring into an abyss” (113) of the “chamber’s alveoli” (Cărtărescu Nostalgia 18) brings clear allusions to Nietzsche’s most famous aphorism from Beyond Good and Evil: “When you gaze long into the abyss, the abyss gazes back into you” (“Wenn du lange in einen Abgrund blickst, blickt der Abgrund auch in dich hinein”; my trans 98). Cărtărescu rejects Nietzsche’s warning about submitting to the power of the abyss and does not just stare into the abyss but relishes and basks in the anti-literary rays of the abyss. The entry wound into Cărtărescu’s vivisection of literature begins with the narrator claiming, “The Roulette Player is a character […] But then I, too, am a character, and so I can’t stop myself from bursting with joy. Because characters never die, they live each time their world is ‘read’” (23). However, anti-Mircea is not “bursting with joy […] each time [his] world is ‘read’”; instead, he cries out “help!” 3,025 times. From Nostalgia to Solenoid, the body of Schrift does not end with closing the final pages as the spine stretches its sinewy muscles, it continues, in absentia, of author, character or reader.

“Write with blood”: Maximalist Hypobiography

In my introduction to this dissertation, I wrote that contrary to Mironescu and Mironescu, the genre and style of Solenoid is not what they coin “maximalist autofiction” (66), but rather what I term maximalist hypobiography. Consequently, in this second section, I want to outline the aesthetics of maximalist hypobiography and how it unfolds in the nightmarish, labyrinthine setting of what anti-Mircea describes as “Bucharest, the saddest city on the face of the earth” (98). However, I must stress that while it is important to note that Solenoid is set in the twilight of Nicolae Ceaușescu’s regime, this dissertation will avoid a historical analysis of Romania’s “late-socialism” (Mironescu and Mironescu 68). There is a deliberate attempt by Cărtărescu to reject how Eastern European works of literature are too often superficially read as responses to the fall of communism and its legacies. Firstly, throughout Solenoid, Ceaușescu is not named; he is represented through the ironic depiction of an unnamed portrait of authority in the classroom; secondly, the phrases socialism and communism appear no more than ten times throughout the text; and finally, the famine, abject poverty, and totalitarian subjugation experienced by Romanian citizens are positioned as secondary to anti-Mircea’s sufferings. Consequently, I want to avoid analysing Solenoid through the lens of anti-communism or post-communist nostalgia. Instead, I will focus on how the style of Solenoid constructs an inescapable labyrinth for the reader, author, and narrator.

The term hypobiography is a neologism that comes from Lyotard’s biography of André Malraux, in which Lyotard “goes beneath the figure and invents an André Malraux” (Williams Political 1). While biography posits an empirical study of a subject’s life from birth to death, hypobiography embraces the fluidity of hypothesis, the what if, or what could have been as a literary alternative to autofiction. In addition to Lyotard’s usage of the term hypobiography, I argue that hypobiography is a term that resonates with Zarathustra’s claim from Thus Spoke Zarathustra: “Of all writings, I love only that which is written with blood. Write with blood” (67). However, in Solenoid, Cărtărescu does not just write with blood to construct a singular hypobiography of his Other self; he uses anti-Mircea as a scalpel that vivisects the body of all literature and spreads it out into a libidinal skin that spans all 638 pages of the novel. Encoded in the narrative are allusions to Kafka, Thomas Mann, Dylan Thomas, Borges, Spinoza, Kant, Marx, Tolstoy, and Joyce, to name a handful; however, by inscribing into the now-flattened libidinal skin of literature, the scalpel becomes a pen, a tattooist’s needle. Anti-Mircea concludes, “You can’t tattoo over old tattoos” (166); every act of writing is cutting into an always-already subject, literature. Therefore, for Cărtărescu and anti-Mircea, literature “is a machine for producing first beatitude, then disappointment” (42). It signifies not escape but the death of affect.

The term maximalism refers to a genre of postmodern literature that emerged in the United States in the late 20th century and then emigrated to Europe in the early 21st century. Texts like Thomas Pynchon’s 1973 Gravity’s Rainbow, David Foster Wallace’s 1996 Infinite Jest, and Zadie Smith’s 2000 White Teeth are considered maximalist works of fiction for the “multiform maximising and hypertrophic tension of [their] narrative[s]” (Ercolino 241). Consequently, when describing Solenoid as maximalist, I draw inspiration from Stefano Ercolino’s 2012 essay “The Maximalist Novel”, where “the maximalist novel seems to be the last, and most refined, literary product of late capitalism” (244). Ercolino’s characterisation of the maximalist novel draws heavily on Jameson’s critiques of postmodernism being the “cultural logic of late capitalism”, signifying a “waning of affect” (11). Jameson argues that postmodern culture signifies a new kind of “aesthetic popularism” (2) that represents an attempt to “think the present historically in an age that has forgotten how to think historically in the first place” (xi). Ercolino stratifies maximalism into ten characteristics, like “Length” (243), the texts often span more than 500 pages, “Dissonant chorality” (248) narration splits into multiple narrative voices or threads, and “hybrid realism”, a trope of antirealist “implausible, grotesque, or even ridiculous” situations, characters, or narratives (253). However, Ercolino’s reliance on Jameson’s critiques of postmodernism leaves his argument blindsided when it comes to analysing the maximalist hypobiography of Solenoid, as it places Cărtărescu in the logic of peripheral late capitalism rather than the semi-peripherality of Cărtărescu’s Romania. This is demonstrated by how Gravity’s Rainbow or White Teeth have “enjoyed considerable success [as] bestsellers” (244); however, Cărtărescu’s reception in anglophone bookstores and academia has been lukewarm at best, for example, only the first volume of Cărtărescu’s maximalist-memoir trilogy Blinding (1996-2006), has been translated into English in 2013.

This dissertation will not follow Ercolino or Jameson’s argument that “the way back to the modern is sealed for good” (156); instead, I will use Lyotard’s earlier 1979 The Postmodern Condition as a more encompassing theoretical framework that recognises that the postmodern is more a mode of disruption, rather than epochal. The English translation of The Postmodern Condition includes a foreword by Jameson in which he claims that Lyotard is advocating for a “return to the older critical high modernism” (xviii). However, Lyotard does not argue that the prefix “post” is a temporal marker for “after” the modern or a desire to return to the modern, but rather a spatial-temporal displacement of the Freudian term Durcharbeitung (working-through). Through this, Lyotard maintains that a “work can become modern only if it is first postmodern. Postmodernism […] is not modernism at its end but at its nascent state” (79). This distinction is imperative as Lyotard maintains that the postmodern occurs before, alongside, and after the modern epoch; the two are inherently entwined. Consequently, Lawrence Sterne’s 1759 Tristam Shandy could be considered to align with Ercolino’s stylistic characteristics of maximalism. Sterne’s text is long; the opening abounds in “narratorial omniscience” (248), and the opening description of Shandy’s birth and conception is “implausible, grotesque, or even ridiculous” (253).

The absurdity of Sterne’s opening is echoed by Lyotard’s hypobiography of Malraux, whose opening is narrated from the position of an 18-month-old Malraux, seeking to get under Malraux’s skin to “make incisions so deep in the skin of reality” (Singed Malraux 102). In Solenoid, Cărtărescu does not seek to get under anti-Mircea’s skin but rather to cut open the body of literature and spread it out into a Moebian labyrinthine skin. Contrary to Malraux’s maxim of the “Museum Without Walls”, anti-Mircea describes how “Literature is a hermetically sealed museum, a museum of illusionary doors” (41); novels are not fantastical escapes from the mundaneness of our lives, but “[n]ovels hold you here, they keep you warm and cosy” (210). For anti-Mircea, novels deny escape from loneliness, failure, and intense and paranoid thoughts. Literature is an inscription onto an always-already discursive palimpsest that does not breed hope but disappointment.

“A book should demand an answer […] But when, for God’s sake, will you read a real book” (210)

Thus Spoke Anti-Mircea.

“Voice of a canary. With the filigree of his speech fills torturously burned-in labyrinthine grooves”: Toward a Libidinal Palimpsest

Throughout Solenoid, just as Virgil guides Dante in The Inferno, Cărtărescu uses Kafka as one of anti-Mircea’s guides towards God, not the Abrahamic God of salvation but a Gnostic God of literature at what he calls the “Last Judgement” (210). Consequently, I want to use an elusive quote from Kafka’s Diaries as a slippery rope to grasp as we traverse the anti-literary libidinal palimpsest of Solenoid. On March 2, 1915, Kafka wrote: “Voice of a canary: With the filigree of his speech fills torturously burned-in labyrinthine grooves” (385). I do not want to decipher the precise meaning of this entry but leave it as a murky riddle that wrangles and coils around this chapter. Instead, I want you, the reader, to see, smell, taste, touch, and hear the homophonous screech of the canary’s “speech” as a sensory evocation for entering a coal mine drenched in soot and sweat. The canary’s warning contorts into speech – go no further, search not deeper, and enjoy the light and air while you can. The canary’s warning dissipates as the poisonous gas fills your lungs, and the abyss seductively whispers:

Are you in despair?

Yes? You are in despair?

Run Away? Want to hide?

(Kafka 5; emphasis added)

The cry of Kafka’s canary is echoed by anti-Mircea in section 20 when he decries at the Last Judgement, “I want you to read on my skin, you, who will never read it, it is a cry, repeated page after page: ‘Leave! Run Away! Remember you are not from here!’” (211); as you run away the canary’s cry mutates into anti-Mircea screaming and tattooing the phrase “help!” (560-567) 3,025 times onto his corporeal manuscript.

“I am nothing but literature.”

In Benjamin’s preface to his translation of Kafka’s Diaries, he argues how Brod “presented the diaries to the extent possible in the guise of a Werk, a cohesive and fixed work, rather than Schrift, writing as a fluid, ongoing, godless activity” (ix). Kafka’s body of Schrift is demonstrated by numerous entries where he laments, “Wrote nothing” (222), “Awful. Wrote nothing today. No time tomorrow” (223), “Nothing, nothing”, “Wrote nothing” (224). Consequently, Kafka’s Diaries are not a complete organic body of Werk, but rather a body of Schrift that has been vivisected and stretched out into a “Moebian-labyrinthine skin [allowing] intensities to run in it without meeting a terminus” (Lyotard LE 4). This is encapsulated by Kafka’s entry on August 21, 1913, when he declared, “I am nothing but literature” (304); however, the literature that Kafka is referring to is not the complete body of Werk that 21st-century anglophone literature dictates, but rather the affective intensities of a body of Schrift. Therefore, in this section, I want to explore how, in Solenoid, Cărtărescu does not just write one singular hypobiography but that Solenoid forks into multiple hypobiographies, with one of the many subjects sewn into the libidinal skin of Solenoid being Kafka.

In 1921, Brod published an appraisal piece titled “The Poet Franz Kafka” (“Der Dichter Franz Kafka”) in the German journal Die neue Rundschau. In this, Brod recalls a conversation between himself and Kafka on the decline of hope in humanity, in which Kafka exclaims that “We are […] nihilistic thoughts, suicidal thoughts that arise from God’s head” (“Wir sind […] nihalistiche Gedanken, Selbstmordgedanken, die in Gottes Kopf aufsteigen” my trans; 1213). Brod then asks whether Kafka interprets these thoughts as indicative of Gnosticism and questions the possibility of any form of hope existing with humanity rather than God. Kafka replies wilily that there is “hope enough, infinite hope — just not for us” (“‘Oh Hoffnung genung, unendlich viel Hoffung — nur nicht für uns’” my trans; 1213). This pithy quote is sewn into the fabric of anti-Mircea’s consciousness when he describes his interactions with the protestor Virgil, “I thought about Kafka: salvation exists, just not for me” (294).

In the wake of Kafka’s death from tuberculosis in 1924, Kafka revealed in two unsent letters to Brod his will for “all these things without exception are to be burned” (qtd in Brod “Postscript” 265). The only intended readers of Kafka’s body of Schrift were fire and ash; Brod ignored Kafka’s will and instead took the title “literary executor” to publish and, more importantly, edit Kafka’s work to the extent that any form of Kafka’s Prague-German dialect was transformed into the territorialised High-German, Kafka’s queerness was removed, and any derogatory comments about Brod were expunged. Brod executed Kafka’s bodies of Schrift and attempted to sew and re-animate its bodily apparatuses into the body of Werk. This is demonstrated by later publications of this conversation regarding hope and God; Brod, in 1954, included the phrase “for God” to render Kafka’s Schrift more religious and Godfearing (Franz Kafka: Eine Biographie 94). The Kafka in Cărtărescu’s Solenoid is emblematic of what Benjamin describes as “Schrift, writing as a fluid, ongoing, godless activity” (xi). Solenoid’s hypobiographical use of Kafka reasserts that which Brod hid in reducing Schrift to Werk. The fluid Schrift writing process that Benjamin describes encapsulates the essence of what both Cărtărescu and anti-Mircea are attempting in Solenoid as exemplified by anti-Mircea’s proclamation that “the book I hold dearest, [is] Franz Kafka’s Diaries” (164).

Cărtărescu is often billed as the Romanian Kafka in anglophone discourse, and it may be superficial to describe a piece of literature as “Kafkaesque” because it has first lost any real meaning. Moreover, because it renders the so-called “Kafkaesque” piece of literature secondary to Kafka. There is, however, something celebratory from Cărtărescu’s perspective in being described as Kafkaesque: from Nostalgia to Solenoid, Cărtărescu has been serenading Kafka. Cotter shares this sentiment, arguing that Cărtărescu is “not stealing from Kafka” but inviting “Kafka to come into the world of Solenoid” and join him at the anti-literary dinner party. In this fictionalised dinner party, you don’t discuss your Werk, and you are warmed by the burning bodies of Schrift in the fireplace.

Toward a Libidinal Palimpsest

In this chapter’s first section, I want to briefly outline Deleuze and Guattari’s theoretical framework of “minor literature” from their 1975 Kafka: Toward A Minor Literature to emphasise why it is neither accurate nor appropriate to describe Cărtărescu’s Solenoid as minor. Deleuze and Guattari explore the term minor literature through a schizoanalysis of Kafka, arguing that “minor literature doesn’t come from a minor language [Kafka’s Prague-German]; it is rather that which a minority constructs within a major language [High-German]” (Kafka 16). They identify three characteristics of minor literature: “the deterritorialization of language, the connection of the individual to a political immediacy, and the collective assemblage of enunciation” (18). However, Kafka’s minoritarian Prague-German does not constitute a minor literature in itself; rather, minor literature only arises through deterritorialising arboreal and territorialised languages, like High-German. Therefore, we can claim that bodies of Werk reinscribe the majoritarian language par excellence, whereas bodies of Schrift are synonymous with minor literature. Consequently, Kafka and his bodies of Schrift only become minor through a deliberate alterity to the majoritarian language. Deleuze and Guattari argue that this is demonstrated most clearly in his diaries: “Kafka deliberately kills all metaphor, all symbolism, all signification” (22). Through this, Kafka’s most poignant reflections on himself are found not in his “finished” and published bodies of Werk, like The Metamorphosis or Brod’s bowdlerised Diaries, but in the unpublishedbodies of Schrift. However, as Cotter notes, Cărtărescu’s Romanian is not minoritarian in Romania (although Romanian is arguably minor in Anglocentric literature), and Cărtărescu has “all the status and cultural capital he can use”. Cărtărescu, unlike Kafka, is not “the epitome of marginalised authors” (Terian 335), but anti-Mircea is certainly marginalised; he represents a fictionalised minor literature or a libidinal palimpsest.

I have chosen Lyotard’s libidinal intensities rather than minor as a deliberate alternative to Deleuze and Guattari’s positive frameworks for mapping the micropolitics of desire. A libidinal palimpsest constitutes a text that embraces Lyotard’s account of libidinal intensities: “Let’s make theory anti-theory” (LE 257), Cărtărescu’s Solenoid functions under the rubric of “let’s make literature, anti-literature”. Lyotard’s libidinal mapping does not depend on its relationship to the majoritarian-Werk but refuses oppositional structures in favour of affective intensities. This is demonstrated by anti-Mircea noting that “I always knew that writing was a palimpsest, scraping away at a page that already contains everything” (486); every act of writing, reading, publishing, and appreciating literature silently repeats the mantra: Affect is Dead! Long Live Affect! The Kafka in Solenoid is not the minor figure of resistance found in DeleuzoGuattarian philosophy, but rather a figure that acknowledges the limitations of literature as an escape from our mundane lives. Kafka is encoded throughout Solenoid’s “labyrinthine grooves” (Kafka Diaries 385) as demonstrated by anti-Mircea’s repetitions from Kafka’s unpublished Schrift, which he claims accounts for his “aversion to the novel […] because not even Kafka dared to transform them into the tiny ear bones of any narrative” (209):

The master of dreams, the great Issachar, sat in front of the mirror, his spine against its surface, his head hanging far back, sunk deep into the mirror. Then Hermana appeared, master of the twilight, and she melted into Issachar’s chest, until she completely disappeared.

(Kafka qtd in Cărtărescu 209)

Anti-Mircea’s body of Schrift approaches this extract from Kafka like a phagocyte approaching an invasive pathogen. The phagocyte engulfs the foreign material, fusing with a lysosome, which releases lysozymes, hydrolysing the Kafka-pathogen and using it to form new proteins, which are then dispersed around the body, the text. Phrases like “the master of dreams” or “the great Issachar” are thus encoded into the protein synthesis of anti-Mircea’s body of Schrift. However, Kafka is not just synthesised through language; the anti-Mircea-Kafka cell is divided to the extent that anti-Mircea is medically tied to Kafka. Anti-Mircea recalls his childhood diagnosis of PPD tuberculosis – the disease that killed Kafka – anti-Mircea survived while Kafka died. The two are linked under what anti-Mircea proclaims: “Too often literature constitutes the eclipse of the writer’s mind and body” (43). This eclipsing of literature is most poignantly elucidated by Kafka’s “Conversation Slips”, where when he was unable to speak, he would communicate on scraps of paper: “Please be careful that I don’t cough in your face”, and the canary returns with the slip “A bird was in the room” (Letters).

Open the so-called Fourth Dimension and Spread Out its Tesseracts

I want to preface this chapter by encouraging the reader to be patient with this chapter and, like anti-Mircea, will attempt to “escape by moving perpendicular to the page of the book” (212) and to display the “incompossibility” (Lyotard LE 11) of representing and entering into the fourth dimension. Therefore, just as Lyotard argues that we must “take Marx as if he were a writer, an author full of affects, take his text as a madness and not as a theory” (95), this chapter will take Solenoid and Libidinal Economy as texts of madness, and wrestle with their affective intra-activity. Consequently, I have structured this chapter as a Möbius strip, oscillating between the unmediated intensities of the libidinal band and the cooling of the band into the theatrical volume of the “disjunctive bar” (Lyotard 14) to analyse how Cărtărescu hypobiography further forks to find escape, not in literature, but in the fourth-dimensional tesseracts of Mathematician Charles Howard Hinton.

Titillate the Page and Scorn the Book

Go to your bookshelf and pick up a book – it doesn’t matter which – and trace your fingers around the front and back; it has three dimensions, right? – length, width, and height. Does the plasticised cover shimmer in the luminescence of your reading light, or does the matte dustjacket deny any prismatic jouissance; stroke the spine and caress its wrinkles; the stench of a hundred always-already thumbed and annotated pages fills the room if it’s old. If it’s new, does the oily scent of stolen labour fog your glassy eyes as the mass-produced dimensionality of literature reminds you that Affect is Dead! Long Live Affect! We enjoy the mass-produced aroma of the book; its umami tang titillates our salivary glands, and the spine’s mucus-like glue begins to crack. Does it flirt with you, seductively whispering, “Open my so-called body of Werk and spread out all my pages”. The book’s intensities are a sensory set of tricks that dissipate as you begin to slow down, read closely, and attempt to inscribe meaning as you become the “[t]he operator of disintensification” (Lyotard LE 14); you fondle the embossed words on the page and splice the libidinal intensities of the body of Schrift into the confines of meaning-making. There is neither an inside nor an outside to the Haut (skin) of the page, but we, good literary critics, demand meaning as we affirm the body of Werk as a three-dimensional “disjunctive bar” (Lyotard 14). Therefore, the book is simultaneously planar and three-dimensional, and in the case of anti-Mircea’s manuscript, Solenoid desperately attempts to stretch into an unrepresentable and incompossible fourth dimension.

Opening the Fourth Dimension.

Although I have played with Lyotard as a mirror simulacrum for approaching this chapter, I want to cool down the libidinal writing style to engage with how Cărtărescu approaches the fourth dimension in Solenoid. In layperson’s terms, three-dimensional space is pivotal for framing our understanding of reality; everything we perceive is composed of length, width, and height. However, this assumption is fallacious as it denies the opaque, the Doppler effect, the trompe l’oeil, the caraway seeds that smell of peppermint, and the monster under the bed. While it may be true to state that our perception of reality is founded in this fixed three-dimensionality, in Solenoid and this dissertation, I am arguing that reality is deceiving and abounds in affects. Through this, anti-Mircea proclaims, “I cannot help but think that reality is just pure fear, frozen fear. I live in fear, I breathe fear, I swallow fear, I will be buried in fear” (322). The adrenaline coursing through your body dilates your pupils, noticing craquelure in the oil painting of reality; as anti-Mircea notes, “If I blink, my life forks” (32). Therefore, the fourth-dimension functions as a dimension experienced by unleashing affects.

Cărtărescu does not choose to write a fictionalised account of his own life in the manner of Knausgård or Ernaux; instead, Solenoid forks, bifurcates, mitoses. As Cărtărescu positions the “intra-activity” (Barad 152) of Kafka and anti-Mircea he also weaves the lives of the Boole family, the Voynich Manuscript, and Hinton as simultaneously intra-acting with anti-Mircea. Anti-Mircea writes a literary biography of Hinton, describing how “he was born a century before me” (350) and a “cerebral haemorrhage put an end to the bizarre life of the explorer of the fourth dimension” (351). Cărtărescu takes inspiration from Hinton’s 1904 The Fourth Dimension, in which Hinton uses Euclidean three-dimensional geometrical models to map how the fourth dimension can be approached through cubes. He posits the parallax of how a two-dimensional being would perceive a three-dimensional being as nothing more than a series of cross-sections; the same logic is applied to three-dimensional beings (like us) when we approach a fourth-dimensional object, we can see its shadow, a “tesseract” (Hinton 159). Consequently, if we take the example of the literary page, the affective intensities demand representative scansion, and it is up to the reader to transform the affective intensities into a more representative dimension, the book itself. When we read, we are constantly attempting to inscribe scansion to the intensities of language, to map them onto what a character is doing in relation to the plot, etc.

However, in Solenoid, Cărtărescu does not take geometry as a fixed medium for understanding reality as he writes, “Geometry always appears out of the amorphous, serenity out of pain and torture” (351). Through this, anti-Mircea denotes how the “tesseract, or hypercube, is the trace left by a cube that moves through a fourth dimension, perpendicular to our world (357). Anti-Mircea intersperses his hypobiography of Hinton with a trance-like poem from 10 years ago “when [he] still believed in literature” of what Breton describes as “[p]sychic automatism in its pure state” (26). He then comments on how a “poet dreams at the incandescent peak of the pyramid of knowledge, where geometry and poetry become happily one” (357). This belief from 10 years ago is indicative of Belgian surrealist essayist and poet Marcel Mariën’s 1944 “Non-Scientific Treatise on the Fourth Dimension”. The thrust of Mariën’s essay is that dreams, poetry, literature, and art are pathways that open into a higher fourth dimension, whereby the “dream is the mind’s mode of activity par excellence” (64). However, the naivete of the younger anti-Mircea leads this chapter into the next section, where I analyse how anti-Mircea has become enmeshed in the nihilistic confines of what Lyotard calls the “great Zero” (5).

Opening “Our Moebian-labyrinthine skin”:

In this part of the chapter, I want to become the literary “operator of disintensification” associated with the “disjunctive bar” (LE 14) to explore how Cărtărescu weaves the affective intensities of the fourth dimension into anti-Mircea’s “Moebian- labyrinthine skin” (4). Through this, I want to draw out Lyotard’s theories in more detail and explore how Lyotard’s libidinal intensities resonate with the affective “intra-activity” (Barad 152) of Cărtărescu’s Solenoid.

As argued in my introduction, Libidinal Economy reinscribes the paradoxical tenet of poststructuralism: critiquing the notion of representation in language through the medium of language. Similarly, in Solenoid, anti-Mircea rejects the comfort and escape from reality that literature supposedly provides through the medium of literature—his manuscript. To avoid regressing into Plato’s cave of representation, Lyotard proposes the vivisection of an ambivalently sexed body and stretching it out into the libidinal band/skin. Therefore, there is a feeling of inundated velocity when reading Libidinal Economy; sentences often span paragraphs, and the concepts Lyotard introduces are not easily clarified; instead, he moves quickly between references and then explains the concepts later in the text. Therefore, the reader is always running to catch up with Lyotard’s style, aesthetics, and concepts.

There is an affective resonance, at least on the level of prose style and the velocity of writing, between Cărtărescu’s Solenoid and Lyotard’s “book of evilness” (Peregrinations 13); Solenoid, like the rest of Cărtărescu’s novels, was handwritten as a single draft, without revision (Self). The persona that Lyotard takes of the “libidinal economist” (11) is not to critique capitalism, as he maintains that there is not an outside to capitalism, and to critique something, one must be outside the subject to critique, a position that is impossible to Lyotard (108). Therefore, as Katie Crabtree argues, Lyotard, the libidinal economist, is “radically self-aware” (244), as is Cărtărescu, in his role as a literary author, unlike anti-Mircea, who is not. Through this, both texts explore the limitations of representation by paradoxically representing their ideas through philosophy and literature. Both texts can, therefore, be considered as libidinally charged attempts at what Breton describes as “[p]sycic automatism in its pure state […] Dictated by the thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.” (26). This notion of an “absence of any control” is pivotal for both Cărtărescu and Lyotard: both texts aim to unleash the affective restraints confined by the great Zero.

Although this dissertation has discussed the space where libidinal intensities first occur, the libidinal band, I want to draw out and attempt to elucidate more of Lyotard’s terms, namely, the bar, incompossibility, and the great Zero, to display the affective “intra-activity” (Barad 152) of both bodies of Schrift. The libidinal band has no beginning nor end, has no singular side or dimensionality, and aleatorily spins to circulate the primary intensities of desire; the band is, therefore, formless and unable to represent anything (akin to molecules in a high-pressure environment), and over the time, the band cools, turning less rapidly and has a volume, this stage of the band, Lyotard terms the “disjunctive bar” (14). Therefore, if we return to my example of the book and the page, the page is akin to the white-hot intensities of the libidinal band, and when it cools down, the page has theatrical volume, the book. However, as good literary critics attempt to excavate meaning and signification, the page cools, loses its libidinal, affective, and aleatory intensities, and is inscribed with our representational interpretations. Cărtărescu alludes to this problem of reading when he writes, “a book assumes an absence […] while it is being written, the reader is missing. While it is being read, the writer is missing” (255). However, the literary critic ignores the absence and attempts to inscribe signification to the intensities on the page whilst also attempting to inscribe signification to the author’s book. To combat the literary critic’s judgemental gaze, anti-Mircea decries after sex with his lover, “I pressed my hands to hers, my hands to her breasts, my lips to her lips […] I don’t believe in books – I believe in pages, in phrases, in lines” (212). Anti-Mircea does not want to live in the ossified affects of the body of Werk that literature demands but instead wants to roam the planar intensities of the libidinal band.

Anti-Mircea’s desire to live outside the “disjunctive bar” (Lyotard LE 14) of books and literature is accentuated throughout Solenoid until he reads about “Boole, Lewis Carroll, Edwin Abbott” (239), thereby unwittingly internalising the dimensional palimpsest of literature. Alluding to Abbott’s satirical 1844 novel Flatland, anti-Mircea writes:

I have read thousands of books but never found one that was a landscape as opposed to a map. Every page of theirs is flat, but life itself is not. Why would I, a three-dimensional creature take as a guide the two dimensions of an ordinary text? Where will I find the cubical page where reality is modelled? […] Only then, through the tunnels of cubes, can we escape the suffocating cell” (Cărtărescu 212)

The thematic parallels between Abbott’s Flatland and Solenoid are displayed in this extract. Flatland describes a world of two-dimensional beings, whereby the protagonist encounters a three-dimensional sphere, which irrevocably changes his worldview. However, the conceit of Abbott’s Flatland is that although the protagonist “Square’s” world seems two-dimensional, it has always, in fact, been three-dimensional. However, he cannot imagine beyond the confines of his flat world. The inability to ascribe signification to this three-dimensional “higher dimension” is reminiscent of how we, as literary critics, cannot ascribe signification to the libidinal intensities of the band without falling back into the Platonic trap of representation. This conundrum is signalled in affect theorist Eugenie Brinkema’s 2014 The Forms of the Affects, where she critiques how affect scholars cling too much to bodies being affected by affects and concludes that “affect […] has fully shed the subject” (25)

In Solenoid, anti-Mircea shares a similar existential crisis to Abbott’s Square, whereby his world becomes flat when he is forced back into the mundane circles of teaching rather than the spheres of scholarly acclaim. Anti-Mircea views The Fall as his escape into scholarly acclaim that should have allowed him to escape the oppressive topology of “Bucharest, the saddest city on the face of the earth” (98). For anti-Mircea, three-dimensionality is a “deceiving trompe l’oeil for the infinitely more complex eye of our mind” (107), and in distinguishing his manuscript from published bodies of Werk claims it “will make the amazing rosebud of the fourth dimension open before us” (107). Anti-Mircea’s belief in his manuscript opening up to the fourth dimension is akin to Mariën’s belief in the ability of art to open the eye to the fourth dimension.

The convergences of the three-dimensional world with the fourth dimension can be read as an example of what Lyotard calls incompossibility, which is used, according to Williams, “to express how absolute difference can occur beyond any reference to a reality or real world wherein all things would be related” (Philosophy 54). Incompossibility refers to how intensities combine dispositifs, the apparatuses that coordinate and deny intensities on the libidinal band and figure, which eludes language but must be reached through language. Therefore, anti-Mircea’s desire to use his manuscript to escape the confines of his three-dimensional prison can be read as emblematic of one of Lyotard’s most puzzling figures, the great Zero. The great Zero is one of Lyotard’s most complicated terms to explain, as placing it into words reinscribes it within the “negative, nihilistic account of desire that has typified Western thought since Plato” (Crome). Yet, its effects are to distintensify and fold the libidinal band back into traditional forms of representation “into a theatrical volume which has an inside and an outside” the great Zero “is thus an empty centre” which reduces complexity and eradicates affect (Grant “Glossary xiii). Crucially, the great Zero does not come before libidinal intensities but denotes the complete slowing down of the libidinal band into a singular narrative or method of representation. Intensities or affects are now at absolute zero, unmoving, at −273.15 °C. The great Zero, therefore, according to Lyotard, renders systems like capitalism and semiotics entirely nihilistic. This is demonstrated when anti-Mircea writes: “The sign doesn’t signify, the index finger does not indicate, they become, for a brain that lacks the power of thought, the thing shown” (164); this encapsulates what Lyotard means by the great Zero, the interior of representation, which signifies nothing but mere shadows. Consequently, anti-Mircea becomes enmeshed in the totalising confines of the great Zero; he cannot escape its nihilistic grip and is trapped in the logic of what Kafka once exclaimed, “Miserable person that I am” (Diaries 299).

“help!”: The Great Ephemeral Trompe L’Oeil:

In the final section of this chapter, I want to uncover the “help!” (560-567) pages of Solenoid and how they can be read as indicative of The Great Ephemeral Skin, “one of Lyotard’s most provocative figures” (Grant “Glossary” xiv). Cărtărescu is deliberately preventing the representational logic of the “disjunctive bar” and the singular nihilistic narrative of the “great Zero”: through the sheer number of repetitions and blocking structure of “help” scansion and representational thinking are denied. The “help!” pages function as trompe l’oeil that exposes the craquelure in the skin of reality and opens the subject to experience fourth-dimensional intensities.

The Great Ephemeral Skin, as Grant so aptly surmises, “[h]ighlights the disruptive potential of the figure, a concern which occupied Lyotard from Discours, figure” (“Glossary” xiv). The thrust of Lyotard’s 1971 Discourse, Figure, that Grant refers to is similar to how Jacques Derrida argues that there is a hierarchical relationship between oral language and written language, as elucidated in his term “différance” (242). However, unlike Derrida, whose argument turns on the inter-relationship of writing to speech, in Discourse, Figure, Lyotard distinguishes between the written text associated with semiotics and structuralism and the phenomenology of the visual, the figure. Lyotard argues that there is a plasticity in the figural, e.g. in paintings or performance arts, whereby the figural is irrevocable to any systemic or linguistic approach to language. Crucially, however, discourses and figures are not binaries; written texts can contain figures, like poetry or metaphor, and equally, figures can become chaotically affective without a discursive structure.

In Libidinal Economy, The Great Ephemeral Skin can be conceived of as resembling a semi-permeable membrane that allows molecules or intensities to cross on a concentration gradient; however, as energy dissipates, the intensities become ossified by the representational logic of the great Zero. Consequently, when we attempt to “read” the “help!” (560-567) pages, traditional representation discursive thinking fails as we see, experience, and feel the words on the page; they blur together and imprint themselves onto our corneas. Additionally, the repetitions of “help!” do not just blur on the page but also through the pages; therefore, when you try and read the words closely, you cannot escape the affects of the figural within the text and its “song of our fearful agony” (560).

Although Lyotard does not discuss the fourth dimension in either Discourse, Figure or Libidinal Economy, he discusses the fourth dimension in his 1977 book on French artist Marcel Duchamp, Duchamp’s TRANS/Formers. Lyotard writes, “Duchamp understands that in working on the 2-dimensional projects, even of 4-dimensional objects, he does not at all emancipate himself from the critique of the senses that is the metaphysical obsession of the Platonic and Christian West – he continues it” (205). Lyotard goes on to argue how Duchamp “affirms representation-narration […]not in order to denounce the illusions of the cave” but that Duchamp affirms that these “are only projections” (205). Similarly, the figural “help!” does not allow the subject to enter into the incompossible fourth dimension but rather projects into it, thus reinscribing that which is denied by the great Zero. We, the reader, writer, and literary critic, are joining anti-Mircea. We are “lifted up, perpendicular to our world, [screaming] the song of agony: help! [x3,025]” (560) into the Cave.

Escaping “this great Zero, what crap!”

I don’t want to conclude this dissertation in the sense of an ending, fin, finis, or Endung, as this dissertation has fundamentally argued against the definitive, conclusive, and the death of affect that bodies of Werk exude. To write conclusively is to the return to the Cave and to thus reinscribe the nihilism of the “great Zero, what crap!” (Lyotard LE 11). Instead, I want to illuminate more affective “labyrinthine grooves” (Kafka Diaries 385) to traverse when wandering – lost – in Solenoid. Firstly, this dissertation has not explored the importance of the fact that both Libidinal Economy and Solenoid are texts read in translation, the intensities of these texts further fork due to Grant and Cotter. Crucially, this divergence can have both good and negative consequences, particularly the latter for Lyotard’s text, as it has suffered in English translation with its influence on accelerationism and Nick Land’s neo-fascist Dark Enlightenment. However, this dissertation has rejected accelerationist readings of Lyotard in favour of reading Lyotard’s text as a body of affect that affects and allows us to be again affected by literature. Secondly, this dissertation has not focussed on how Cărtărescu opens up the body of Schrift to propel more agent in this intra-acting dynamism of forces (Barad 141), like The Voynich Manuscripts, Nicolae Vaschide, and Judge Schreber. Lastly, this dissertation has not explored the surrealist aesthetics of Solenoid, like the sequence of colours from an oil spill being replicated in a student’s prismatic nails or the dream diaries of anti-Mircea.

Instead of these “labyrinthine grooves” (Kafka Diaries 385), this dissertation has followed how Solenoid functions as a nebula of affective intensities that attempt to affect the reading subject to combat the mantra, Affect is Dead! Long Live Affect! Through this, I have explored how Solenoid can be categorised as maximalist hypobiography as a genre that embraces the fluidity of hypothesis in the engulfing tendrils of late-capitalist maximalist fiction. Secondly, I have explored how the Kafka in Solenoid escape the great Zero that Brod’s bowdlerised body of Werk dictated and re-configured Kafka as one of the many agents sewn into the libidinal skin of Solenoid. Lastly, this dissertation has attempted to “move perpendicular to the page of the book” (Cărtărescu 212) to show how Lyotard’s models of the band and bar can be used to emphasise the incompossibility of the fourth dimension and the importance of being affected by literature, rather than folding its affects into the theatre of representation. I, therefore, want to end (?) on how like the figures that appear at the foot of anti-Mircea’s bed in the ephemerality of sleeping/waking, Cărtărescu’s Solenoid will remain with me as I sleep, eat, dream, cry, see, hear, smell, and scream the elegy of “help!” (560) into the abyss.

Works Cited

Abbott, Edwin A. Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions By a Square, Oxford UP, 2007.

Bass School at UT Dallas, “Mircea Cărtărescu’s ‘Solenoid’, a reading and conversation with Sean Cotter.” YouTube, 11 Apr 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XaH411mqw5E.

Barad, Karen. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Duke UP, 2007.

Benjamin, Ross, “Translator’s Preface: Glimpses into Kafka’s Workshop”, The Diaries, by Franz Kafka, Schocken Books, 2022, pp. vii-xxiii

Borges, Jorge Luis. “The Garden of Forking Paths.” Ficciones. Edited by Anthony Kerrigan, translated by Helen Temple and Ruthven Todd, Grove Press, 1962, pp. 89–101.

Breton, Andrè. “Manifesto of Surrealism.” Manifestos of Surrealism. Translated by Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane. U of Michigan P, 1969. pp. 1–48.

Brinkema, Eugenie, The Forms of the Affects, Duke UP, 2014

Brod, Max. “Der Dichter Franz Kafka.” Die neue Rundschau, vol. 32, no. 2, November 1921, pp. 1210-1216, Internet Archive, accessed 14 Apr 2024, https://archive.org/details/die-neue-rundschau-32.1921-bd.-2/page/1212/mode/2up

—.Franz Kafka: Eine Biographie, Schocken Books, 1954, Internet Archive, accessed 14 Apr 2024, https://archive.org/details/franzkafkaeinebi00brod/page/n4/mode/1up

—.“Postscript”, The Trial, by Franz Kafka, Schocken Books, translated by Willa Muir and Edwin Muir, pp. 265-267, 1995

Cărtărescu, Mircea. Blinding: Volume 1, translated by Sean Cotter. Archipelago Books, 2013.

—. Nostalgia, translated by Julian Semilian. Penguin Books, 2013.

—. Solenoid, translated by Sean Cotter. Deep Vellum Publishing, 2022.

Cohen, Nili. “The Betrayed(?) Wills of Kafka and Brod.” Law and Literature, vol. 27, no. 1, 2015, pp. 1–21. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26770737.

Cotter, Sean. “Interview”. Conducted by Joseph Bamford, March 7 2024

Crabtree, Katie. “Chapter 17 Libidinal”. Keywords in Radical Philosophy and Education. Edited by Derek. R Ford, Brill, 2019, pp. 242-254

Crome, Keith. “Lyotard’s Libidinal Economy: Affective Nihilism, Capitalism and the Libidinal Skin.” 2022, Bloomsbury Philosophy Library, http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350892996.005

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, translated by Brian Massumi. U of Minnesota P, 1987.

—. Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, translated by Robert Hurley, Mark Seem and Helen R. Lane, Bloomsbury, 1977, 2013.

—. Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature, translated by Dana Polan, U of Minnesota P, 1986.

Derrida, Jacques. Margins of Philosophy, translated by Alan Bass, Harvester P, 1982.

Eagleton, Terry. Literary Theory: An Introduction, 2nd ed, U of Minnesota P, 1996.

Ercolino, Stefano, “The Maximalist Novel”, Comparative Literature, vol. 64. no. 3, 2012, pp. 241-256, DOI: 10.1215/00104124-1672925

Grant, Iain Hamilton, “Glossary”, Libidinal Economy, by Jean-François Lyotard, Indiana UP, 1993, pp. x-xvi

—.“Introduction”, Libidinal Economy, by Jean-François Lyotard, Indiana UP, 1993, pp. xvii-xxxiv

Hinton, Charles Howard. The Fourth Dimension. Celephaïs Press, 2004.

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, Or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, Verso, 1991

—.“Foreword”. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. By Jean-François Lyotard, Manchester UP, 1984, pp. vii-xii

Kafka, Franz. Franz Kafka: Tagebücher: Kommentarband. Edited by Hans-Gerd Koch, Michael Müller and Malcolm Pasley, Fischer Verlag, 1990.

—. Letters to Friends, Family, and Editors, translated by Richard and Clara Winston, Schocken Books, E-Book, 2013.

—. The Diaries of Franz Kafka. Translated by Ross Benjamin, Schocken Books, 2023.

—. The Lost Writings, translated by Michael Hofmann, New Directions, E-Book, 2020

Lyotard, Jean-François. Discourse, Figure, translated by Antony Hudek and Mary Lydon, U of Minnesota P, 2011

—. Duchamp’s Trans/Formers, translated by Ian McLeod. Leuven UP, 2010.

—. Libidinal Economy, translated by Iain Hamilton Grant. Indiana UP, 1993.

—. Peregrinations Law, Form, Event: The Wellek Library Lectures at the University of California, Irvine. Columbia UP, 1988.

—. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, translated by Geoffrey Bennington and Brian Massumi, Manchester UP, 1984

—. Signed, Malraux, translated by Robert Harvey, U of Minnesota P, 1999

—. Signé Malraux, Grasset, 1996

Mariën, Marcel. “Non-Scientific Treatise on the Fourth Dimension.” The Surrealism Reader: An Anthology of Ideas. Edited by Dawn Ades, Michael Richardson and Krzystof Fijalkowski, translated by Michael Richardson and Krzystof Fijalkowski. Tate Publishing, 2015. pp. 59–64.

Mironescu, Doris and Andreea Mironescu. “Maximalist Autofiction, Surrealism and Late Socialism in Mircea Cărtărescu’s Solenoid.” The European Journal of Life Writing vol. 10, 2021, pp. 66-87, https://doi.org/10.21827/ejlw.10.37605

Nouvet, Claire, Julie Gaillard, and Mark Stoholski. “Introduction.” Traversals of Affect: On Jean-François Lyotary. Edited by Julie Gaillard, Claire Nouvet and Mark Stoholski, Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 1-18, 2016

Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm. Jenseits von Gut und Böse: Vorspiel einer Philosophie der Zukunft, edited by Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, de Gruyter, 2014

—. Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book For Everyone And No One, translated by R.J. Holldingdale, Penguin Books, 1961, 1969

Self, Will. “The Galaxies Within: The mind-bending fiction of Mircea Cărtărescu”, The Nation, 17/24 Apr 2023, https://www.thenation.com/article/culture/solenoid-novel-mircea-cartarescu/

Sterne, Laurence, The life and opinions of Tristram Shandy, gentleman, Penguin, 1967

Terian, Andrei. “The Poetics of Hypercycle in Mircea Cărtărescu’s Solenoid” Life Writing, vol. 9, no. 3, 2022, pp. 323–340, Project MUSE, https://doi.org/10.1080/14484528.2020.1747351

Weir, Matt. “Mircea Cărtărescu Stares Down the Abyss.” Dissent, vol. 70, no. 1, 2023, pp. 112–118.

Williams, James D. Lyotard: Towards a Postmodern Philosophy, Polity Press, 1998.

—. Lyotard and The Political, Routledge, 2000

[1] Hypobiography appears only in the original French (Lyotard Signé Malraux 355)

- Hypobiography appears only in the original French (Lyotard Signé Malraux 355) ↩︎